6 March, 2023

Welcome to this week’s JMP Report

Last week we saw two stocks trade on the local bourse, BSP and KSL. BSP traded 809,081 shares trading higher to close the week out at K13.00 per share while KSL saw 19,079 shares, trading lower to close the week out at K2.74

Refer details below

WEEKLY MARKET REPORT | 27 February, 2023 – 3 March, 2023

| STOCK | QUANTITY | CLOSING PRICE | CHANGE | % CHANGE | 2021 FINAL DIV | 2021 INTERIM | YIELD % | EX-DATE | RECORD DATE | PAYMENT DATE | DRP | MARKET CAP |

| BSP | 809,081 | 13.00 | 0.20 | 1.54 | K1.4000 | – | 13.53 | THUR 9 MAR 2023 | FRI 10 MAR 2023 | FRI 21 APR 2023 | NO | 5,317,971,001 |

| KSL | 19,079 | 2.74 | –0.01 | –0.36 | K0.1610 | – | 9.93 | FRI 3 MAR 2023 | MON 6 MAR 2023 | TUE 11 APR 2023 | NO | 64,817,259 |

| STO | 0 | 19.10 | – | – | K0.5310 | – | 2.96 | MON 27 FEB 2023 | TUE 28 FEB 2023 | WED 29 MAR 2023 | YES | – |

| KAM | 0 | 0.95 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | YES | 49,891,306 |

| NCM | 0 | 75.00 | – | – | USD$0.035 | – | – | FRI 24 FEB 23 | MON 27 FEB 23 | THU 30 MAR 23 | YES | 33,774,150 |

| NGP | 0 | 0.69 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 32,123,490 |

| CCP | 0 | 1.90 | – | – | – | – | 6.19 | – | – | – | YES | 569,672,964 |

| CPL | 0 | 0.95 | – | – | – | – |

4.20 |

– | – | – | – | 195,964,015 |

Dual listed stock PNGX/ASX

BFL – 5.39 +29c

KSL – .745 -3c

NCM – 24.07 +1.46

STO – 7.20 +19c

The Alternatives 7 days

Gold 1856 +2.5%

Oil – 79.75 +4.51%

Bitcoin – 22426 -5.17%

Ethereum 1561 -4.41%

PAX Gold 1847 +2.68%

What we’ve been reading this week

BMW Launches Pilot Hydrogen Fuel Cell-Powered Car Fleet

Mark Segal February 28, 2023

BMW Group announced the launch of the BMW iX5 Hydrogen pilot vehicles, a fleet of demonstration cars powered by hydrogen fuel cells. The fleet will go into service this year, deployed internationally for demonstration and trial purposes.

The launch of the pilot hydrogen fleet comes as BMW aims to reduce CO2 emissions per vehicle over the full lifecycle – including supply chain, production and product use – by at least 40% by 2030. While most of the company’s focus is on the transition to battery electric vehicles, with a plan for 50% of company-wide sales to be EVs by 2030, the company said that it views fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) technology as “a potential addition to the drive technology used by battery-electric vehicles.”

Oliver Zipse, Chairman of the Board of Management of BMW AG, said:

“Hydrogen is the missing piece in the jigsaw when it comes to emission-free mobility. One technology on its own will not be enough to enable climate-neutral mobility worldwide.”

BMW said that the launch of the new hydrogen vehicle follows four years of development work, with the BMW iX5 Hydrogen first unveiled as a concept vehicle in 2019. The company sources the individual fuel cells for the vehicles from Toyota, who has been collaborating since 2013 with BMW on fuel cell drive systems. BMW Group produces the fuel cell systems for the pilot fleet at its in-house competence centre for hydrogen in Munich, and the company also developed special hydrogen components for its new fuel cell system, including a high-speed compressor with turbine and a high-voltage coolant pump.

The vehicles can store nearly six kilograms of hydrogen in in two 700-bar tanks made of carbon-fibre reinforced plastic, providing the vehicles with a range of over 500 km.

In a statement announcing the launch of the pilot fleet, BMW Group said:

“With the right conditions, hydrogen fuel cell technology has the potential to become a further pillar in the BMW Group’s drive train portfolio for local CO2-free mobility.”

Oliver’s insights – nine key lessons for today from the 1970s, 80s and 90s

Dr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Economics and Chief Economist, AMP Investments

Key points

– The experience of the high inflation 1970s and its aftermath hold key lessons for today. In particular, that once high inflation becomes entrenched in expectations that it will stay high, inflation is very hard to get back down but also that there are lags in the way monetary policy impacts.

– Whether the RBA and other central banks have done enough is a judgement call. The RBA is signalling that it has not yet done enough so more rate hikes are on the way. Our view is that the RBA has likely already done enough. Upcoming retail sales and jobs data are critical in this.

Introduction

In 1981 on a holiday with my parents to Hawaii we got into a discussion with some Americans about their new President, Ronald Reagan, and they said he had to deliver some tough economic medicine after years of policy mismanagement. At the time I dismissed them, but as the years went by I concluded that they had a point. The 1970s were an economic mess as inflation was allowed to get out of control. In fact, things were so bad that there was a wave of nostalgia for the 1950s and early 60s when things seemed a lot better – starting with American Graffiti, Happy Days, Laverne and Shirley and the rise of retro radio stations playing hits from the 50s and 60s. With inflation surging lately, what lessons can be drawn from the 1970s and its aftermath in terms of today’s problems. This is important because if we don’t learn the lessons of the past, we are bound to repeat them. This is particularly pertinent now as I often hear the comment “why are we so worried about a bit of inflation?” and “why is the RBA inflicting so much pain?”

What went wrong in the 1970s?

But first it’s worth a brief recap. From around the mid-1960s inflation started rising. First in the US and then in Australia. It was driven by a combination of tight labour markets, more militant workers demanding higher wages, a big expansion in the size of government, disruption from the Vietnam War, easy monetary policies, social unrest and years of industry protection reducing competition and pushing up prices. It really blew out after the OPEC oil embargo of 1973 and the second oil shock after the Iranian revolution of 1979. The surge in inflation came in waves, reaching double digit levels. It also combined with frequent recessions as policy makers tightened monetary policy in response to high inflation but were too quick to ease when growth slumped only to see inflation take off again driving more tightening and another economic downturn. The end result was a decade of high inflation, high unemployment and slow economic growth from which it took a long time to recover. For investors it was bad as high inflation meant high interest rates, high economic volatility & uncertainty and reduced earnings quality all of which demanded higher risk premiums to invest (& low PEs). The 1970s were one of the few decades to see poor real returns from both shares and bonds.

Source: ABS, AMP

Source: ABS, AMP

So what broke it?

The malaise ultimately ended after voters turned to economically rationalist political leaders – like Thatcher, Reagan and Hawke and Keating in Australia. The policy response involved:

- tight monetary policy which drove severe recessions, ultimately culminating in inflation targeting;

- supply side reforms like deregulation, privatisation & competition laws to make it easier for the economy to meet demand;

- this was aided by globalisation and then in the late 1990s the tech boom – which boosted the supply of low-cost goods and services;

- in Australia, the prices and incomes Accord between Government, unions and business helped break the wage price spiral at the time.

This all broke the back of inflation with some in the 2000s calling it dead.

Key lessons

There are several lessons from the malaise of the 1970s and its aftermath and early 1990s recession in Australia for the inflation problem of today:

- What won’t work. First, the experience of the 1970s and 1980s provides a clear list of things that won’t work to solve the problem:

- Higher wage growth to keep up with inflation – this just perpetuates high inflation making it harder to get back down.

- Price controls – these were tried, eg, in the early 1970s in the US. But they restrict supply and when removed inflation was worse than ever.

- Replacing the RBA Governor – doing this mid-way through the problem would risk shaking confidence in the RBA’s anti-inflation commitment at the worst time likely resulting in even higher interest rates. The US saw something similar in the 1970s when it replaced William Martin at the Fed with Arthur Burns which just perpetuated high inflation.

- Raise the RBA’s inflation target – this would also reduce confidence in its ability to get inflation down and mean higher interest rates.

- Shift responsibility for inflation control back to government – this sounds fine in theory as governments have more levers to pull (eg it could impose a 1% temporary income tax surcharge to cool demand which would spread the load more fairly beyond those with a mortgage). But unfortunately, politicians have shown an inability to inflict the pain necessary to slow inflation. So, it doesn’t work in practice. It was the way things were done in Australia in the 1970s and its failure led to the widespread adoption of central bank independence focussed on meeting an inflation target.

- Containing inflation expectations is key. Once inflation takes hold it gets harder to squeeze out. This relates to “inflation expectations”. Once inflation has been high for a while consumers and businesses expect it to stay high and so behave in ways – via wage demands, price setting and acceptance of price rises – that perpetuate it. A wage price spiral is a classic example of this where prices surge, workers demand wage rises to compensate which boosts costs & drives a new round of sharp price rises. This is an example of the “fallacy of composition” – while it is rational for an individual to demand a wage rise to match inflation if all workers do so it just leads to a further surge in prices.

- Whether its supply or demand, central banks have to respond. While the initial impetus to a surge in inflation may be constrained supply if it occurs when demand is strong or goes on for too long, central banks still have to respond to cool demand and signal they are serious about containing inflation. Central banks failure to do this after the 1973 OPEC oil shock contributed to inflation getting entrenched in the 70s.

- Avoid stop go monetary policy. There is a danger in easing monetary policy too early in a downturn if inflation expectations have not been tamed. This occurred in the 1970s with inflation slowing and central banks easing as growth slowed but inflation soon rising even higher. This underpins talk central banks will keep rates “higher for longer”.

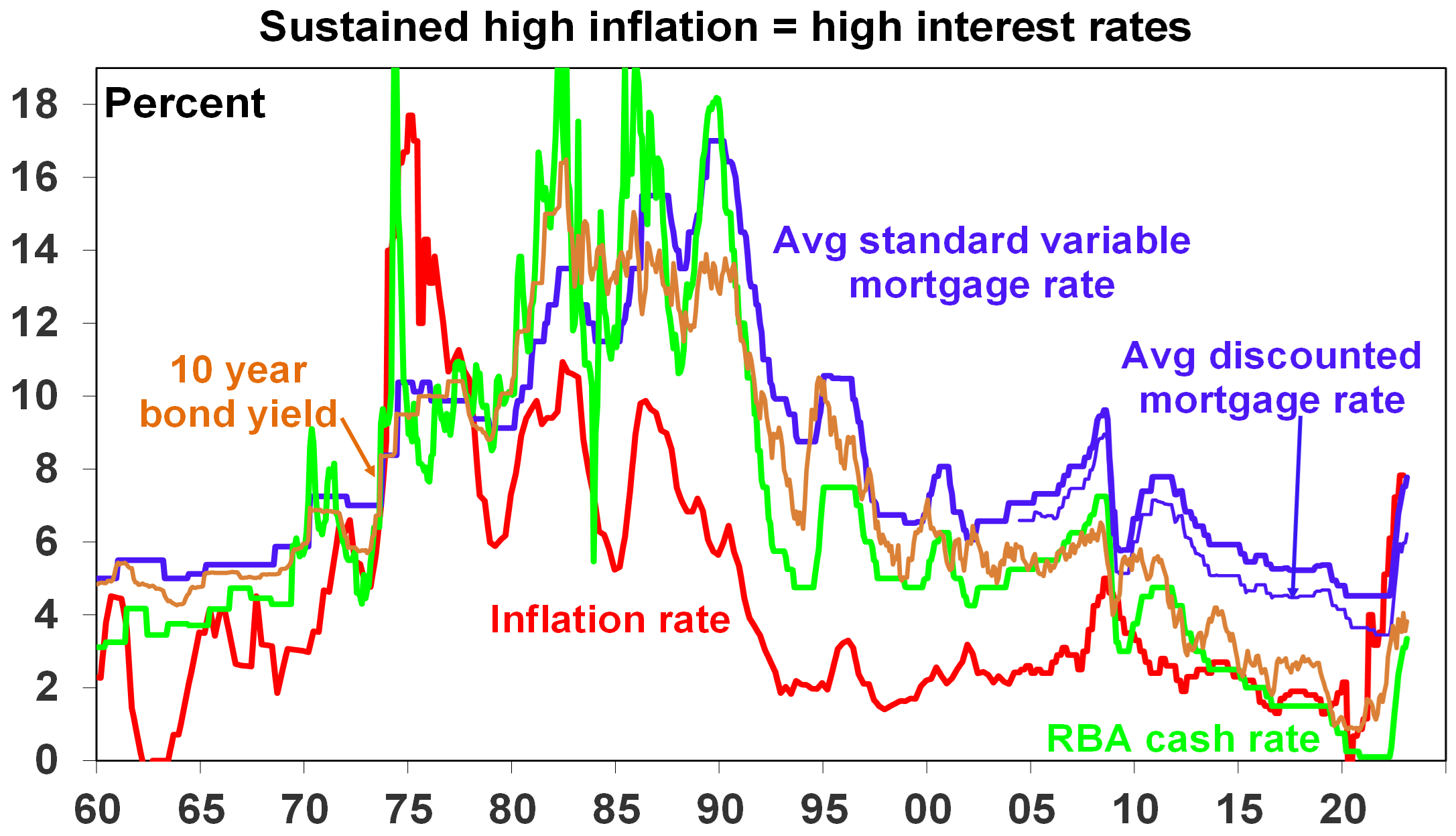

- Entrenched high inflation will mean entrenched high interest rates. This is because investors will start to demand compensation for the fall in the real value of their savings by demanding higher rates. So interest rates rose through the 1970s into the 1980s. And this of course weighs on the valuation of shares and property. 10-year bond yields of around 3.5% to 4% are fine if investors expect inflation will fall to say 2-3% but if they believe inflation will stay high at 6-8% then they are too low.

Source: ABS, AMP

- Entrenched high inflation is bad for the economy. Because it distorts economic decisions it can cut economic growth as in the 1970s, add to economic uncertainty which hampers investment & boost inequality.

- Once entrenched high inflation risks requiring a deep recession to remove it. This was seen in the deep recessions of the early 1980s and early 1990s in Australia which saw double digit unemployment. This was because by the late 1970s inflation expectations in the US as measured by the University of Michigan consumer survey were running around 10% following years of very high inflation making it harder to get inflation down. Australia was likely similar.

- Governments should focus on the supply side. The practical inability of governments to adjust fiscal policy much to control inflation means the best it can do in the short term is not add to the problem and this means reducing budget deficits and limiting new spending. Longer term there is a lot that government can do to help control inflation and its all about supply side reform to make the economy work more smoothly, ie deregulate, cut back government and competition reforms. Unfortunately, the political appetite for such reforms is low.

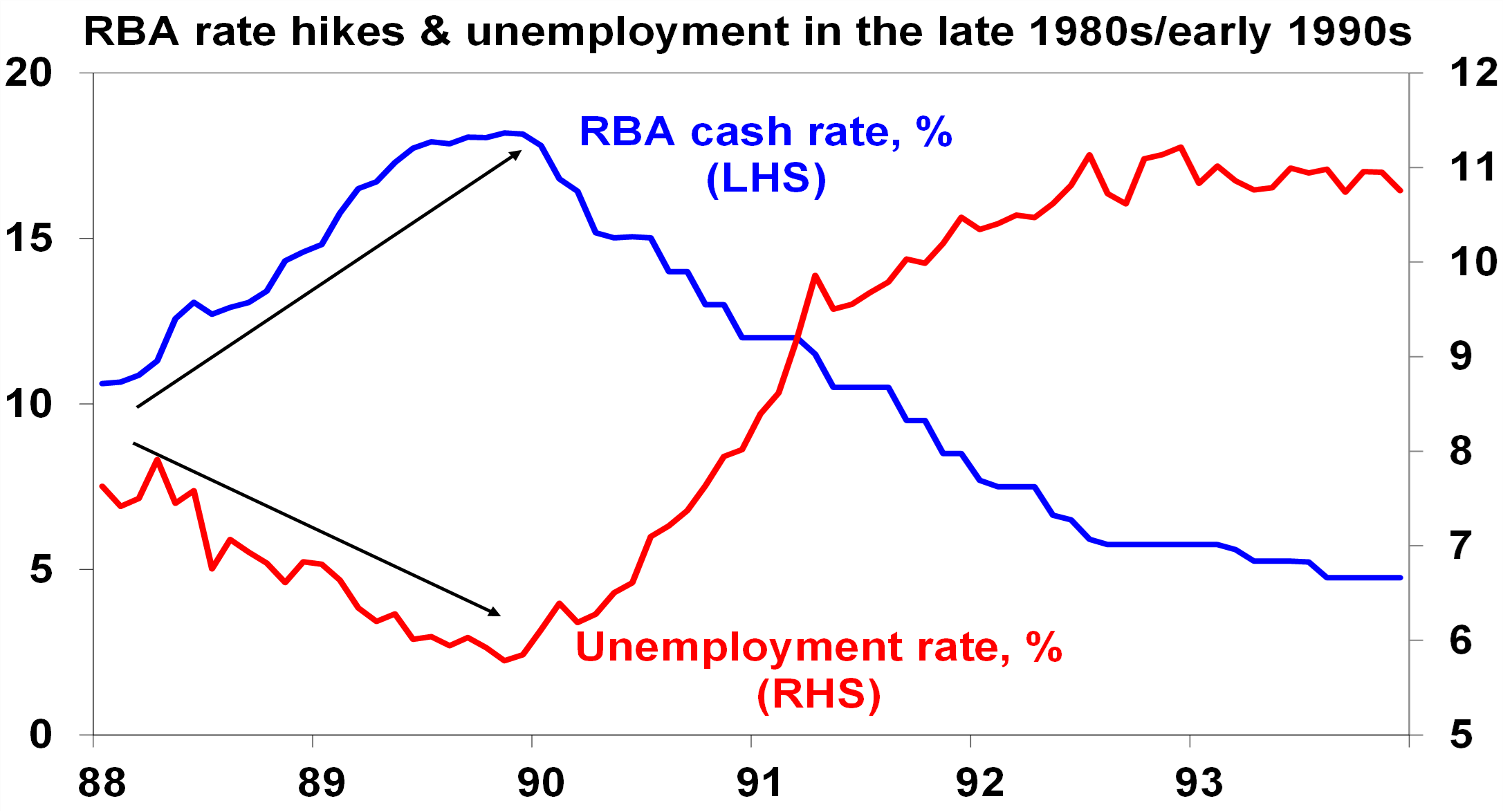

- Monetary policy operates with a lag. The early 1990s recession showed monetary policy works with a lag. This seems contradictory to the fourth point above but highlights the risk of overtightening. The lags arise as it takes time for rate hikes to be passed on to borrowers, that to slow spending and then for slower demand to lead to less employment and the flow on of this back to households and for all of this to cool inflation. This can take 12 months or more. So just looking at inflation and jobs data can be misleading as they are lagging indicators. In the late 1980s the RBA kept hiking and unemployment kept falling. But by early 1990 it was clear it had gone too far.

Source: ABS, RBA, AMP

So what does it all mean for today?

The good news is that this is not 1980 and more like the early 1970s: inflation expectations are low; there is no evidence of a wage price spiral, notably in Australia; supply bottlenecks, freight costs and surging money supply which led inflation are now reversing; and high household debt ratios compared to the 1970s should make monetary policy more potent. But the lessons from the 1970s explain why central banks are so fearful of letting inflation get out of control and also the difficult balancing act facing them. As RBA Governor Lowe said they “are managing two risks…not doing enough [resulting in high inflation persisting & proving costly later] [and] that we move too fast, or too far” and trigger recession. Balancing these two risks is seen as resulting in a narrow path to low inflation and the economy continuing to grow. But what is too much or too little tightening is a judgement call. The RBA’s view has become more hawkish after the December quarter CPI and is signalling at least two more rate hikes and money markets and the consensus of economists have moved to reflect this with consensus rate expectations rising above 4%. Our view is that the RBA risks doing too much given the high vulnerability of a significant minority of indebted Australian households and that the impact of past rate hikes is just being masked by normal lags accentuated by revenge spending associated with reopening. Signs of slowing consumer spending and jobs growth along with there still being no evidence of a wages breakout in Australia are consistent with this. As such, it risks a re-run of the late 1980s/early 1990s experience where Australia was inadvertently knocked into a deep recession as the lagged impact of rate hikes took time to show up. So, while we believe rates are close to the top, the RBA’s tough guidance means that the risks are skewed to the upside. Further evidence of a slowing consumer and jobs data are necessary to cause the RBA to rethink so upcoming retail sales and jobs data are critical in this.

Many elements to consider when investing in a Listed Investment Company

Jessie Hamilton

Wilson Asset Management

NTA is an important first step, but don’t stop there.

Key points

- A LIC’s Net Tangible Assets is an important piece of information for LIC investors.

- The NTA represents the LIC’s true underlying value and can be compared with the LIC’s share price.

- The NTA should be assessed in context with other LIC information, such as its portfolio performance and dividend record.

Recent equity market volatility has presented investors with opportunities to buy listed investment companies (LICs) at a discount to their underlying net tangible asset (NTA) backing.

To help make an informed investment decision, it is important not only to look at the NTA of a LIC, but also to assess the company’s investment strategy, long-term investment portfolio performance, quality of the investment manager, history of paying fully franked dividends and how the company communicates and engages with its shareholder base.

Understanding NTAs

In their simplest form, the NTA per share of a LIC represents the total assets of a company, less liabilities and intangible assets (such as goodwill), divided by the number of shares on issue.

The NTA represents the true underlying market value of the company’s assets, calculated in accordance with the Australian Accounting Standards, at a point in time.

A LIC is a public company, has a board of directors, corporate governance and its shares are traded on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX).

At times, the LIC’s share price can fluctuate above or below its underlying NTA value. The NTA of a LIC is announced on the ASX to shareholders each month.

The NTA of a company is a “right now” reflection of where the assets of the LIC are invested, how much those investments and other assets the company holds are worth, less any associated liabilities for the company.

Companies often report a pre-tax and post-tax NTA, showing shareholders the value of the company excluding current or deferred tax liabilities and assets as well as the value of the company’s assets if those tax liabilities were to be paid.

Fundamentals first

NTAs are a point-in-time reference for the value of a LIC and should always be the first step for investors when evaluating the company.

However, NTAs are a small slice of the pie when it comes to making an informed investment decision with LICs. It is important also to consider:

- the company’s historical investment portfolio performance, which may be a measure of the investment manager’s ability to perform compared to its relevant index on a like-for-like basis (noting that past performance is not indicative of future performance)

- the NTA growth of the company, as this demonstrates the realisable value of the company after expenses, fees and taxes

- the total shareholder return (TSR), which measures the tangible value shareholders gain from share price growth and dividends paid over the period, before the value of any franking credits distributed to shareholders through fully franked dividends.

At the end of the day, TSR is the true return for shareholders of a LIC, as it represents the tangible value they are able to receive for their shares, including dividends paid by the company.

The TSR can often be impacted by a company’s shares trading at a discount or premium to its underlying NTA, so it is important that you consider all three measures of performance for a LIC when making an informed investment decision.

Why are some LICs at premiums and others at discounts?

A LIC can trade at a premium or discount to its underlying NTA. An investor, for example, might be able to buy $1 of assets for 80c – or sell $1 of assets for $1.20.

Whether a LIC trades at a premium or discount to its NTA can be influenced by a number of factors including, but not limited to:

- short-term falls in domestic or global equity markets and overall equity market volatility

- the performance of its investment portfolio

- its history of fully franked dividend payments

- its marketing and communication strategy

- the overall experience of its investment management team and board of directors.

Buying shares at a discount to NTA means you pay less today than what the company’s underlying net assets are valued at. It can give shareholders access to a portfolio of investments for less than what they are worth, but investors need to be confident that the discount can dissipate over time in order to capture or realise that return.

Buying shares at a premium, however, means you pay more today for a company than its underlying net assets are worth.

LICs can trade at a premium when they pay a consistent and growing stream of fully franked dividends, have a track record of long-term investment portfolio performance, treat shareholders equitably and communicate consistently and effectively with their shareholder base.

The risk is whether that premium to NTA will be maintained or grow over time. Paying $1.20 today for a LIC which has a NTA of $1.10 can quickly lead to an investment loss if the share price of the LIC trades back to its NTA value or goes to a discount.

Putting this information into practice

The closed-end structure of a LIC provides investors with the ability to buy shares at a discount or potentially sell their shares when they are trading at a premium to their underlying net asset value.

However, it is important to not get caught in a “value trap”, referring to situations where a LIC represents good value with its discount to NTA, but falls short of expectations if that discount persists or worsens over time.

There are several risks to consider here, as a LIC may continue to trade at a discount to its underlying NTA for a long period of time. Or the share price premium to NTA of a LIC may evaporate quickly for no other reason than a change in market sentiment or equity market volatility.

Investors should always ask: is there a realistic expectation that the discount will close? Has the LIC traded at NTA or a premium to NTA in the past? And do you believe that the investment manager and the company will be able to close the discount and continue to perform for shareholders?

We believe there are four critical elements of a successful LIC, including a strong record of investment portfolio performance, paying a stream of fully franked dividends, treating shareholders equitably and with respect, and strong shareholder communication and engagement.

It pays to have conviction and take a holistic approach when assessing whether a particular LIC is right for you.

Carbon Fact of the Week

Heating up limestone in a kiln via the process called calcination accounts for about 4% of global CO2 emissions.

Cement is produced by heating limestone and a source of silicon, either clay or shale, in a kiln at 2000°C. Like cement, lime is produced by heating limestone, yet solely, at 900°C.

But unlike cement, lime mortars and its related products “re-absorb” CO2 emissions during their production process which can result in negative-zero (-2%) carbon emissions.

I hope you have enjoyed the read this week and we look forward to assisting you on you investment journey.

Regards,

Chris Hagan.

Head, Fixed Interest and Superannuation

JMP Securities

Level 1, Harbourside West, Stanley Esplanade

Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea

Mobile (PNG):+675 72319913

Mobile (Int): +61 414529814