20 December 2021

Welcome to this week’s JMP Report.

Welcome to this week’s Weekly Report, the final report for 2021. We would like to thank you our clients for your business and we look forward to assisting you with your investment needs in 2022. I hope you have enjoyed the Weekly Report throughout 2021, I try to make it interesting and informative.

Most of the news this week was focused on the close out of Oil Search Shares and the Listing of Santos in its place. The trading code for Santos will be STO. The week also saw the beginning of the holiday season with a very quiet week.

On the trading front, good volume was seen in BSP 1,000,000 shares exchanging hands, gaining .25t to close at K12.25. KSL saw 20,906 shares closing down .30t to close at K2.70. CPL saw some good volume, trading 211,933 to finish flat at .95 while NCM saw a token trade of 30 shares, closing unchanged at K75.0.

|

WEEKLY MARKET REPORT 13.12.21 – 17.12.21 |

|||||||||||

| STOCK

|

QTY |

OPENING |

CLOSING |

CHANGE | 2021 Final Div | 2021 Interim | Yield % | Ex Date | Record Date | Payment Date | DRP |

|

BSP |

1,000,000 |

12.30 |

12.25 |

-0.05 | 1.05 | 0.39 | 11.76% | Fri 24 Sept | Mon 27 Sept | Mon 18 October | No |

|

KSL |

20,906 |

2.70 |

3.00 | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 8.38% | Wed 01 Sept | Thurs 02 Sept | Fri 01 Oct | No |

|

OSH |

– |

10.80 |

– | – | 0.00 | – | – | ||||

|

KAM |

– |

0.99 | 0.99 | – | 0.04 | 0.06 | 10.00% | Wed 15 Sept | Mon 20 Sept | Thur 20 Oct | Yes |

|

NCM |

30 |

75.00 |

75.00 |

– | 0.00 | – | 0.00% | Thu 26 Aug | Fri 27 Sept | Thurs 30 Oct | |

| NGP | – | 0.70 | 0.70 | – | 0.00 | – | 0.00% | Fri 17 Sept | Fri 24 Sept | Mon 01 Nov | |

|

CCP |

– |

1.68 |

1.68 | – | 0.18 | 0.05 | 13.45% | Fri 1 Oct | Fri 8 Oct | Fri 26 Nov | Yes |

|

CPL |

211,933 |

0.95 |

0.95 |

– | 0.00 | – | 0.00% | ||||

What we have been reading this week

What are we reading

To Close the year out, a very good Review of 2021 and Outlook for 2022 from our friends at AMP Capital and some light reading on Magic of mangroves The plant that sequesters more CO2 than rainforest from the Saudi Green Initiative and I have attached the Low Carbon Pulse from our friends at Ashurst.

Download Ashurst, Low Carbon Pulse

Review of 2021, outlook for 2022 – recovery to continue as we hopefully learn to live with covid

Oliver’s Insights – AMP Capital

Shane Oliver, Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

2021 was again dominated by the coronavirus pandemic, along with concern about higher inflation and monetary tightening but shares, unlisted assets and balanced growth super funds saw strong returns.

Continuing solid economic growth, rising profits and still easy monetary conditions should result in good overall investment returns in 2022, but they are likely to be more constrained and volatile than in 2021.

The main things to keep an eye on are: coronavirus; inflation; US politics; China tensions; a possible Russian invasion of Ukraine; inflation; & the Australian election.

2021 – another year of covid

Just as 2020 was dominated by coronavirus so too was 2021. But 2021 turned out to be a far better year for investors. The big negatives of 2021 were of course dominated by coronavirus:

- Coronavirus mutated into more transmissible variants, drove 3 new waves of cases globally, saw more cases & deaths than in 2020 & saw long lockdowns in east coast Australia.

- Inflation in the US and some other countries rose to levels not seen in decades as the pandemic drove a surge in demand for goods, but left supply struggling to keep up.

- Related to this energy prices – notably gas in Europe and coal in China – surged as a result of energy shortages.

- Bond yields surged and many central banks moved to reduce monetary stimulus (by slowing bond buying) and some actually raised interest rates.

- Chinese growth slowed sharply as a result of policy tightening and an associated property downturn.

- Geopolitical tensions continued to simmer – notably between the US and China but also involving Russia & Iran.

- Political uncertainty around the transition of power in the US from President Trump gave way to relative calm with most of the action being in the Democrat party itself.

- And there was plenty to distract long term investors with meme stocks, cryptos and SPACs attempting moon shots and calling into question traditional ways of investing. We have seen it all before though, but cryptos (or rather blockchain) remind us that technology is a regular disruptor, there is lots of spare cash & many are happy to speculate.

However, despite the dominance of coronavirus and other sources of worry and noise there were significant positives:

- Science and medicine started to get the upper hand against coronavirus: vaccines were rolled out with 55% of the global population (75% in developed countries and 79% in Australia) having had a first dose substantially reducing serious illness; and several new treatments further holding out the promise of reducing serious illness from covid.

- This in turn enabled an easing in restrictions (or gradual reopening) albeit it was like 2 steps forward and 1 back.

- Fiscal stimulus, pent up demand and ultra-easy monetary policy helped support household and business spending.

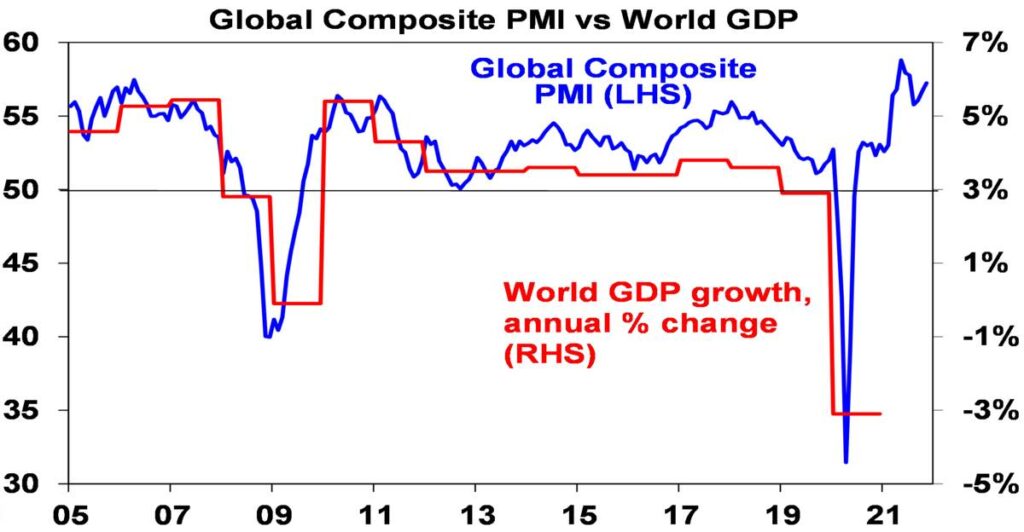

As a result, global GDP is expected to have grown nearly 6% in 2021, in comparison to 2020’s slump of -3%. And in Australia GDP is expected to have risen by 4.5% despite a setback in the September quarter after slumping -2.2% last year. This in turn underpinned strong gains in profits and dividends. As a result, investment markets also performed better than feared, despite covid, higher inflation and higher bond yields.

- Global shares had a few pullbacks as a result of covid and inflation fears, but they were relatively mild and stocks were boosted by strong profit growth, low interest rates and optimism vaccines would allow a more sustained reopening.

- However, US shares remained a surprising outperformer and emerging market shares fell, perhaps as payback for strong gains last year and as Chinese growth slowed.

- Australian shares underperformed with tensions with China not helping – but they actually did better than we expected.

- Government bonds had poor returns as yields rose as central banks moved towards the easy money exits.

- Real estate investment trusts had spectacular rebounds following last year’s hit to property space demand and rents.

- Unlisted property & infrastructure returns rebounded.

- Home prices surged thanks to ultra-low rates, incentives and FOMO. That said, monthly price gains have slowed.

- Cash and bank term deposit returns were poor.

- After rising to our end 2021 forecast of $US0.80 in February the $A fell as the iron ore price fell, the Fed became more hawkish and China tensions persisted.

- Due to solid share and property returns offsetting soft returns from bonds and cash, balanced super funds have seen strong returns – providing payback for a weak 2020.

2022 – from pandemic to endemic

First the bad news: uncertainty over covid remains high and a new variant (Omicron or another) could cause an upset; inflationary pressures will be high for a while; the Fed is expected to raise rates three times; the RBA is expected to start hiking in November taking the cash rate to 0.5% by year end as the conditions for higher rates (inflation sustained in the target range, full employment & a 3% pace in wages) are likely to have been met; and political risk may have more impact.

In terms of politics: the mid-term elections in the US will likely see the Democrats lose control of Congress; French and Australian elections have potential to cause volatility (although Macron is ahead in France and the policy differences between the Government and ALP in Australia are minor compared to 2019); and tensions with China (over Taiwan), Russia (with a risk that it undertakes an invasion of southern Ukraine) and Iran (over its nuclear ambitions) are likely.

However, there is good reason for optimism about continuing economic recovery in the year ahead. First, while coronavirus remains a threat it appears to be having a far less negative impact on economies as vaccines and treatments get the upper hand. While uncertainty remains around Omicron and booster vaccines may need to be tweaked – it appears to be more transmissible but less deadly and if this is confirmed and if it comes to dominate other variants it could help hasten a progression to learning to live with coronavirus like the flu.

Second, excess savings of around $US2.3trn in the US and $250bn in Australia will provide an ongoing boost to spending.

Third, while monetary policy will start to tighten it will still be easy. Some easing in inflationary pressure as production increases and consumer demand swings back to services will provide central banks with breathing space and rate hikes in Europe and Japan are still years away. It’s usually only when monetary policy becomes tight that it ends the economic cycle and the bull market in shares and that’s a fair way off.

Fourth, inventories are low and will need to be rebuilt which will provide a boost to production.

Fifth, positive wealth effects from the rise in share and home prices will help boost consumer spending.

Sixth, the Chinese Government looks to be becoming more focussed on boosting growth, so more policy easing is likely.

Finally, while business surveys are down from their highs, they remain strong consistent with good growth.

Source: Bloomberg, IMF, AMP Capital

Overall global growth is likely to be around 5%, down from 2021 but still strong. In Australia, recovery from the recent lockdowns supported by excess saving, strong business investment & high confidence levels suggest growth of around 5.5%. This is likely to support profit growth albeit at a slower pace than in 2021.

Implications for investors

Still solid economic growth, rising profits and still easy monetary conditions should result in good overall investment returns in 2022 but they are likely to be more constrained and volatile.

Global shares are expected to return around 8% but expect to see the long-awaited rotation away from growth & tech heavy US shares to more cyclical markets in Europe, Japan & emerging countries. Inflation, the start of Fed rate hikes, the US mid-term elections & China/Russia/Iran tensions are likely to result in a more volatile ride than 2021. Mid-term election years normally see below average returns in US shares and since 1950, have seen an average top-to-bottom drawdown of 17%, usually followed by a stronger rebound.

Australian shares are likely to outperform (at last) helped by stronger economic growth than in other developed countries, leverage to the global cyclical recovery and as investors continue to search for yield in the face of near zero deposit rates but a grossed-up dividend yield of around 5%. Expect the ASX 200 to end 2021 back around 7,800.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

- Still very low yields & a capital loss from a rise in yields are likely to again result in negative returns from bonds.

- Unlisted commercial property may see some weakness in retail and office returns, but industrial is likely to be strong. Unlisted infrastructure is expected to see solid returns.

- Australian home price gains are likely to slow with prices falling later in the year as poor affordability, rising fixed rates, higher interest rate serviceability buffers, reduced home buyer incentives and rising listings impact.

- Cash and bank deposits are likely to provide very poor returns, given the ultra-low cash rate of just 0.1%.

- Although the $A could fall further in response to coronavirus and Fed tightening, a rising trend is likely over the next 12 months helped by still strong commodity prices and a decline in the $US, probably taking it to around $US0.80.

What to watch?

The main things to keep an eye on in 2022 are as follows:

Coronavirus – new variants could set back the recovery.

Inflation – if it continues to rise and long-term inflation expectations rise, central banks will have to tighten aggressively putting pressure on asset valuations.

US politics – political polarisation is likely to return to the fore in the US posing the risk of a deeper than normal mid-term correction in shares. However, US political gridlock is usually good for shares.

China issues are likely to continue – with the main risks around its property sector and Taiwan.

Russia – a Ukraine invasion could add to EU energy issues.

The Australian election – but if the policy differences remain minor a change in government would have little impact.

AND SOME HOLIDAY READING FOR YOU

Magic of mangroves: The plant that sequesters more CO2 than rainforests

We’re barely scratching the surface when it comes to the benefits of mangroves. But if they’re so useful, what’s stopping us from planting them everywhere?

Red mangroves growing in the Red Sea off the coast of Saudi Arabia

(Cecilia Martin/ The Red Sea Development Company (TRSDC))

As a plant, mangroves aren’t really much to look at. Clustered around the brackish waters of estuaries, a floating mop of messy green foliage is all you see from afar. It’s only when the tide goes out, and the tangle of knotted roots appears, that you really see the whole thing.

One of the first western records of this plant appeared in the works of Pliny the Elder, the Roman author and naturalist who lived between AD23 and AD79. He had never seen plants that could grow on water, and wrote of his discovery: “on the Red Sea, the trees are of a remarkable nature”.

Almost 2,000 years later, scientists are still discovering remarkable things about these plants, like the fact that they can sequester more CO2 than rainforests, says Professor Carlos Duarte, a leading marine ecologist at Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (Kaust), and they’re barely scratching the surface.

Indeed, there is still much we don’t know about mangroves, including precisely how many species of plants there are. Conservative estimates place the figure at around 50, but this can go up to more than 100 depending on who you consult and how the plants are classified. The core requirement is that it’s a tree or a shrub that’s able to live in the salt-rich and oxygen-poor waters of tropical and subtropical climates. Exactly how it does this varies, too.

Take for example the Rhizophora stylosa, an elongated plant found in Asia where it’s commonly known as the stilted mangrove. Its root is made up of three distinct layers of material that act as fine filters to remove as much as 90 per cent of the salts from the water before it enters the plant – a feature that could feed into the development of more effective desalination filters in future.

Meanwhile, if you look closely at the Avicennia marina, the grey mangrove, it’s often possible to spot salt crystals on the underside of its leaves. This species, the most prevalent variety around the world, has a similar salt filtration system in its roots but it’s not nearly as effective. Perhaps just 50 per cent of the salt is removed from the water before it enters the plant. The rest is stored in the leaves or bark, while any excesses are excreted through its leaves, just like sweat.

Another differentiator between mangroves and other plants is that most of their roots are above ground, some branch out from trunks like stilts while others erupt from the earth like stalagmites – or a spike pit if you’re being really imaginative – but always exposed during low tide rather than hidden below ground. This aerial root network not only helps to secure the plant in place against the bashing waves but it also increases the mangrove’s oxygen uptake from the water.

Grey mangroves growing in the Red Sea off the coast of Saudi Arabia

(Cecilia Martin/The Red Sea Development Company (TRSDC))

To complete their adaptation to their uniquely challenging habitat, all mangroves have leaves with waxy surfaces that lock the moisture in and automatically adjust their position to avoid the searing sun.

Defender of habitats

If mangroves’ unusual physiology isn’t enough to convince you of their remarkable nature then their myriad of other benefits surely will.

Thanks to their density and network of gnarly roots, mangroves are known for reducing beach erosion by holding the soil in place. Any sediment that washes in with the tide – and this includes, Professor Duarte says, the microplastics that are now so pervasive in the ocean – then gets trapped in this ever-expanding network of filters. Over time, as the clarity of the water improves, this sheltered environment becomes a nursery ground for fish and shellfish, which in turn help to support a rich ecosystem of marine life.

Above ground, mangroves are equally indispensable. They create environments suitable for other plants, including rare orchids, as well as insects, birds, lizards and even larger mammals like monkeys and tigers. This rich tapestry creates endless possibilities for scientific research.

In the Arabian Peninsula, for example, there are bees that harvest pollen exclusively from mangroves. Free from pesticides, these plants provide an uncontaminated source of food for the bees – so perhaps it’s no surprise that the bee population in Saudi Arabia is one of the few that’s not in decline. Scientists are now looking at sequencing the genes of these bees, says Professor Duarte, to better understand how colonies in other parts of the world can be protected.

Another field of study is the health benefits of mangroves; in particular, how it could be used in the treatment of breast cancer and other illnesses.

Red mangrove flowers growing in the Red Sea off the coast of Saudi Arabia

Red mangrove flowers growing in the Red Sea off the coast of Saudi Arabia

(Cecilia Martin/ The Red Sea Development Company (TRSDC))

For populations that live along the shoreline, mangroves also act as a first line of defence against extreme weather phenomenon, such as cyclones and tsunamis, something that’s happening with increasing regularity as a result of climate change.

Professor Duarte was among a team of experts working with the UN to assess the damage to coastal areas in south-east Asia following the devastating Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami in 2004, where nearly a quarter of a million people lost their lives. One surprising discovery they made was that those who lived in areas with mangroves suffered considerably less damage.

“Those villages where pockets of mangrove remain between the village and the ocean actually had almost no loss of human lives, and the losses of infrastructure were much less,” he explained. “So the mangroves are also the first line of defence for shorelines against cyclones, against tsunamis and against sea level rise.”

The value of mangroves are of course well known to communities that live near these protective forests. Professor Duarte cites the example of the Mekong Delta, where much of the mangrove forest was destroyed through the use of herbicides and napalm by US forces during the Vietnam War between 1955 and 1975. Recognising the importance of the resource, the Vietnamese people “took it upon themselves to replant the mangroves” after the war.

Red mangrove seedling grows in the waters of Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea

Red mangrove seedling grows in the waters of Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea

(Cecilia Martin/The Red Sea Development Company (TRSDC))

“They planted 1,700 sq km of mangroves in the 10 years after the war,” Professor Duarte adds, “which remains the most significant ecosystem restoration ever attempted by humans.”

Nature’s cleaner

The restoration work completed by the Vietnamese people did more than just safeguard their future, it also benefited the environment at large.

One study from 2011 estimated that a single hectare of mangrove forest stored an average of 1,025Mg C (1,025 tonnes of carbon) . This is around four times that of tropical rainforests and, based on the World Bank’s estimates of CO2 emissions per capita, is enough to offset a year’s worth of emissions for 228 people. In the case of Vietnam, the mangroves that were restored by the 1980s were enough to offset five years of carbon emissions for the entire country, Professor Duarte says.

The mangrove’s carbon sequestering abilities come in two folds, the first being the CO2 stored in the plant itself. The second is through its network of roots, which allow microbial mats to grow in their sheltered crevices. These mats are constantly sucking in the CO2 from the atmosphere to create oxygen, so much so that you can actually see clusters of bubbles.

Just a few years ago, scientists discovered a third way that mangroves can eliminate carbon emissions: by using acids produced by their roots to dissolve carbonate rock such as limestone. This reaction turns carbon dioxide into a carbonate – a salt – and stops it from being released into the atmosphere.

It’s a particularly exciting discovery for Saudi Arabia, where there’s a drive towards reducing emissions as part of the Saudi Green Initiative, and where a large number of mangrove forests grow on limestone bases.

Mangroves in danger

But mangroves have been in decline.

The global conservation body, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), has had mangroves on its red list of threatened species since 2008. While not yet endangered like many of the other species on the red list, mangroves are facing multiple threats as a result of human activity.

Red mangroves growing in a tidal creek on the coast of Saudi Arabia

Red mangroves growing in a tidal creek on the coast of Saudi Arabia

(Cecilia Martin/ The Red Sea Development Company (TRSDC))

Around the world, mangroves are being cut down to make way for residential or commercial developments along the coast. The land has also been cleared to establish agriculture and aquaculture sites that even when abandoned, can’t easily be restored as mangrove forests. The repercussions of this are felt worldwide, not just locally.

Professor Duarted explained: “When we think about climate change we always think about fossil fuels but 38 per cent of the excess carbon in the atmosphere does not come from burning fossil fuels – it comes from messing up ecosystems like losing forests, losing mangroves and losing other ecosystems that reduce the carbon.”

This is one of the reasons why we need to act now, rather than in 60 years, “when we really need the carbon benefits.”

Establishing a forest

In a climate context, growing mangroves on a large scale is actually much more sustainable than other types of forests, as they don’t need any fertilisers or additional water resources. And of course, mangroves’ coastal habitat means there’s never danger of fires, unlike its counterpart on land.

“We see many forests that were planted or protected as part of carbon credits go away in smoke, with wild forest fires in many areas of the world like Brazil or Australia or California,” Professor Duarte says. “Whereas this is simply not going to happen with mangroves.”

All mangroves need to thrive is a suitable coastal location, and that’s the crux of it – mangroves need to expose their roots at least once a day to absorb oxygen from the air and this only happens in the intertidal zone, the band of coastal land that’s under water at high tide and exposed during low tide. In Saudi Arabia, this band is generally less than 100m, compared to other parts of the world where it might be several kilometres.

As a result of rising sea levels, mangrove forests might migrate to higher ground over time, to escape their flooded habitat – a process that could and perhaps should be manually accelerated, says Professor Duarte – but this assumes that there aren’t any coastal developments to impede this shift.

Red mangroves growing in the Red Sea off the coast of Saudi Arabia

Red mangroves growing in the Red Sea off the coast of Saudi Arabia

(Cecilia Martin/ The Red Sea Development Company (TRSDC))

And for Saudi Arabia, and other desert environments, there’s also the problem of camels. In a landscape devoid of almost all greenery, mangroves can be a vital source of food for these voracious eaters. But it’s actually not the grazing that damages the plants – instead, the camels can accidentally trample young plants and roots as they feed, which in turn can be detrimental to future growth of the forest.

Despite these challenges, the trend of losing mangroves on a global scale is now beginning to be reversed, says Professor Duarte. In Saudi Arabia especially, there’s a concerted effort to establish new forests on both the Gulf and the Red Sea coast.

Saudi Aramco started planting mangroves in the early 1990s, for example. Under the Saudi Green Initiative, it has pledged to plant 100 million mangrove trees, contributing towards the nation’s ambitious 10 billion trees target.

More recently, the Red Sea Development Company has been working to establish its own forests as part of the Red Sea Project. Further south, there’s conservation work to enhance the mangrove forests in the Unesco-protected Farasan Islands Marine Sanctuary. And in the north, there’s also potential to establish mangrove forests in Neom, a sustainable city near the border of Jordan, which marks one of the northern-most regions where mangroves can grow in the country.

The Saudi Arabian Ba’a Foundation, a non-profit organisation that preserves endangered species and natural habitats, as well as the country’s cultural and historical sites, is also testing the possibility of planting mangroves north of the Jeddah Islamic Port – one of the busiest maritime facilities in the region.

If this pilot succeeds, it could create many wonderful opportunities to grow mangroves near all the industrial shipping ports, says Nouf Alaskar, operating officer at the Ba’a Foundation.

This effort demonstrates how the vision of the Saudi Green Initiative can be executed, says Alaskar. As Saudi Arabia creates economic opportunities, local leaders from the private and public sectors, including Kaust and its subsidiary consultancy team, the Beacon Development Company are working together to ensure that natural environments are not impeded.

“With the help of mangroves, the Alarbaeen Lake that is adjacent to the port will be cleaned and brought back to its natural state,” says Alaskar.

Increased developments make Professor Duarte optimistic about opportunities for the field, especially after seeing how the Vietnamese government was able to produce impressive results with very basic means.

“If I wasn’t a trained macro-ecologist,” he says, “I would have thought that I was in a pristine mangrove forest, so that tells us that it’s possible to restore mangroves at scale.”

It’s a testament to the resilience of these plants – we just need to give them a helping hand.

The Saudi Green Initiative is Saudi Arabia’s whole-of-government approach to combat climate change.

Learn more about the initiative here

Well that’s where I will sign off for the year, I hope you all have a very happy, safe and enjoyable XMAS and wishing you a wonderful 2022.

Regards

Chris Hagan,

Head, Fixed Interest and Superannuation

JMP Securities

Level 1, Harbourside West, Stanley Esplanade

Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea

Mobile (PNG):+675 72319913

Mobile (Int): +61 414529814