5 December, 2022

Hello and welcome to this week’s JMP Report

In the share market last week we saw four stocks trade on the local bourse, BSP, STO, NCM, and CCP. BSP traded a total of 62,608 shares closing unchanged at K12.41, STO saw 1,282 shares trade also unchanged at K19.10. NCM traded 51 shares trading K1 lower at K74.00 while CCP traded 15,120 shares closing 5t higher at K1.90 per share.

Refer details below

WEEKLY MARKET REPORT | 28 November, 2022 – 2 December, 2022

| STOCK | QUANTITY | CLOSING PRICE | CHANGE | % CHANGE | 2021 FINAL DIV | 2021 INTERIM | YIELD % | EX-DATE | RECORD DATE | PAYMENT DATE | DRP | MARKET CAP |

| BSP | 62,608 | 12.41 | – | – | K1.3400 | K0.34 | 11.61 | FRI 23 SEPT | MON 26 SEPT | FRI 14 OCT | NO | 5,317,971,001 |

| KSL | 0 | 2.88 | – | – | K0.1850 | K0.0103 | 7.74 | MON 5 SEPT | TUE 6 SEPT | TUE 4 OCT | NO | 64,817,259 |

| STO | 1,282 | 19.11 | – | – | K0.2993 | K0.26760 | – | MON 22 AUG | TUE 23 AUG | THU 22 SEPT | – | – |

| KAM | 0 | 0.95 | – | – | – | – | 10.00 | – | – | – | YES | 49,891,306 |

| NCM | 51 | 74.00 | –1.00 | -1.35 | USD$0.075 | K0.70422535 | – | FRI 26 AUG | MON 29 AUG FEB | MON 29 AUG | – | 33,774,150 |

| NGP | 0 | 0.70 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 32,123,490 |

| CCP | 15,120 | 1.90 | 0.05 | 2.63 | K0.134 | – | 6.19 | THU 16 JUN | FRI 24 JUN | THU 28 JUL | YES | 569,672,964 |

| CPL | 0 | 0.95 | – | – | K0.04 | – |

– |

THU 5 APR | THU 14 APR | FRI 29 APR | – | 195,964,015 |

Dual Listed PNGX/ASX

BFL – 4.84 -6c

KSL – .865 steady

NCM – 21.09 +$1.06

STO – $7.15 -10c

Our book has us as nett buyers of BSP and sellers of KSL – If you would like to discuss your investment requirements or how you go about commencing a trading account, please contact chris.hagan@jmpmarkets.com

Last week we saw the 2023 National Budget delivered which has left many scratching their heads. The budget has increased the Company Tax rate on banks from 30 to 45%. The effect will be widely felt including Superannuation Members through reduced dividends. More to come from JMP on how this will impact shareholders.

On the interest rate front, we have the 364 day TBill average remaining steady at 4.30% with BPNG issuing a further 96mill than what was originally on offer.

On the interest rate front, BSP leads the banks in the 12 month money offering 1.35%. In the Finance Company Sector, CCP is at 3.1% and Moniplus at 3.60% for 12mths.

Alternative Assets

WTC – 85.57

Gold – 1,809

Silver – 23.25

Bitcoin – 17231 up

Ethereum – 1,290 up

BNB – 295 up

ETH – 1246 up

What we’ve been reading this week

WHAT IS MORAL HAZARD?

Posted | 02/12/2022 Article from Ainslie Bullion

“Show me the incentives, and I’ll show you the outcome.”

– Charlie Munger, Berkshire Hathaway

‘Moral Hazard’ is a core concept in Austrian economics which describes how individuals and businesses can receive misleading economic incentives.

The classic case of moral hazard came in 2009 when banks on the brink of collapse were bailed out with public funds. Leverage led to outsized profits in the good times, but losses were socialised in the crash. By increasing their risk profile, bank executives were able to pay themselves generous bonuses and stock options. No bankers went to jail, barely any of them lost their jobs, and the circus rolled on. The message this sent to banks in the aftermath… risk it all, and that’s exactly what they have done since 2009 as the global derivatives market has continued to balloon, making the entire system more and more fragile and susceptible to systemic collapse.

Without the real threat of bankruptcy and executives going to jail, there is little reason to save for a rainy day. Another example was the bailout of the airlines in the wake of the 2020 pandemic scare. On 27 March 2020, the US Congress approved $25 billion in taxpayers dollars to prop up 10 major passenger airlines. In the 10 years prior to the pandemic however, the top five US Airlines spent an average of 96% of their free cash flow on share buy backs to pump their stock price and the executives bonuses as a result. If directors and executives were to be held responsible for the fallout in a crisis, then they might have kept back a little more of that free-cash flow. Perhaps they knew that Uncle Sam would always have their back if things ever turned out badly.

As a simplistic example, a cashier in a supermarket is skimming a small amount of petty cash each week. It seems like a great way of raising some extra cash for as long as it lasts. However, when the manager finds out, they are required to repay the stolen money and lose their job. They are now in a much worse financial position than they started, and the meager gains weren’t worth risking the whole enterprise.

Imagine a world though, where rather than the manager reacting like that, the staff member claimed that they had a mental illness, and as a result, the manager gives them a promotion. They have kept all the winnings, and even come out ahead. What has the employee learnt, that stealing and lying have no real negative consequences, so long as the truth is never found out.

Every time banks such as Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) risk the farm and then are bailed out by governments or Central Banks, it rewards excessively “risky business”. In traditional capitalism where free and open markets are the norm, bankruptcy is a healthy part of a functioning free market.

Speaking in the Hidden Secrets of Money Episode 2, Mike Maloney explains how the incentives for politicians are always to spend on public works and welfare, in the process diluting the value of the currency and weakening society as a whole. In the short term, they retain popularity and power, in the long-term… well, that’s someone else’s problem once they are out of office. The skill of politics is to kick the can down the road, and just hope that you aren’t the one holding the bag when the road ends (as all roads must) or the ‘chickens come home to roost’.

Over time, individuals and businesses become more and more dependent on ever increasing government stimulus just to keep going. Government starts as a very small percentage of GDP, and over time it comes to define the economy.

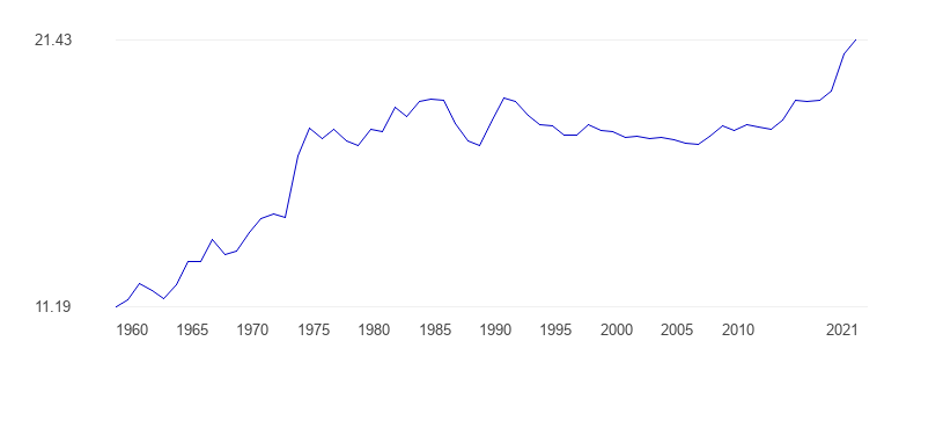

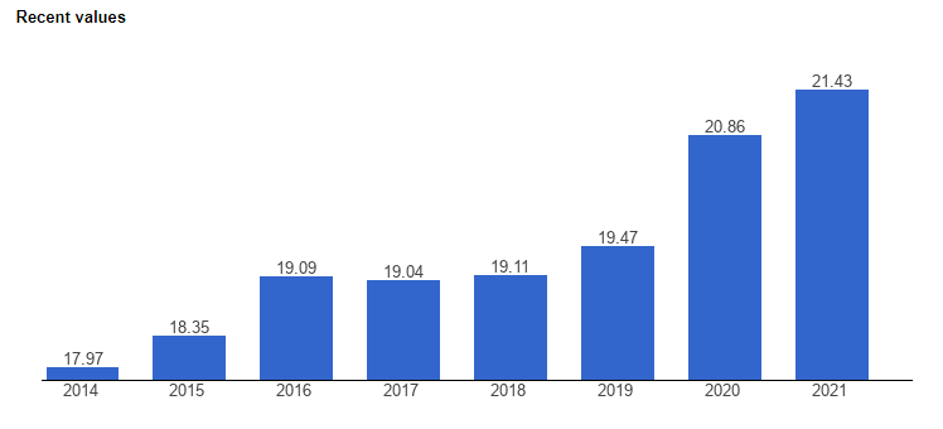

In the early 1960s, government spending was only 11% of GDP, but this has stretched out to more than 21% in 2021. The last five years have certainly seen a quickening.

These figures may not tell the whole story however, as the 2020-21 lockdowns saw vast areas of the Australian economy shut down completely, surely government spending would have been significantly higher as a percentage during that period.

This additional government largesse is only possible through currency devaluation. The government itself doesn’t create additional goods and services, it taxes businesses generating profit, then taxes their employees on their income, and then taxes those employees when they spend their money at, you guessed it, businesses that provide goods and services.

So why does moral hazard matter? In the words of Wall Street legend Charlie Munger of Berkshire Hathaway, “show me the incentives and I’ll show you the outcome”. Central banks, the governments that enable them, and the politicians seeking re-election in the near future, all have incentives to devalue currency and reduce the purchasing power of everyday savers. There is no incentive for them to institute long term reforms and take the pain in the short term for the benefit of the system as a whole.

We often talk about ‘kicking the can down the road’. The only problem is, we may be reaching the end of the road. One scenario is that deposits in banks are bailed in, or their value is severely reduced when transitioning from the old system to the new system – whatever that new monetary regime may be. When banks looked like going under in the GFC, the Australian Government gave a guarantee, but since then, the bail-in laws have ensured that in the next liquidity crisis, the final victim will be the unsecured creditor i.e YOU… the bank depositor with a savings account.

For more information, please see one of our most popular articles of all time, (more than 100,000 views: Bank Bail-ins in Australia: Why your cash isn’t safe

Thank you Ainslie Bullion for this article

Dealing with market volatility and losses

Fri 02 December 2022 – Rachel Waterhouse, Australian Shareholders’ Association

Avoid panic or acting in haste when global equity markets dip.

Key takeaways

- Occasional bear markets are a normal part of share investing. There will always be periods when global equity markets fall.

- A clear investment plan can help investors stay calm when sharemarkets are volatile and avoid the risk of crystallising losses at the worst time.

- Sound finance advice and consideration of tax issues are other key aspects of successful long-term investing.

“Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one.” – Charles Mackay.

It’s a cliché, but equity markets can be a rollercoaster ride.

One day everything is looking fine, then things can turn nasty, and back again, as investors react to the slightest bit of news, stocks rise or fall based on almost insignificant information, and the markets generally continue being predictably unpredictable.

Markets fluctuate between overvaluation and undervaluation like a pendulum on an old clock, depending on whether the herd of investors is feeling optimistic or pessimistic.

Yet, those swings do not happen like clockwork and an inordinate amount of time is wasted attempting to predict such things.

In the 19th Century, Scottish journalist Charles Mackay described this kind of behaviour as the “madness of crowds”, in a series of books looking at various economic bubbles, erroneous beliefs, and other “popular delusions”.

His writings pioneered crowd psychology and have been a bit of a predictor of what can happen – for example, US investor Bernard Baruch apparently learned enough from Mackay’s writings to sell all of his stocks before the Wall Street Crash in 1929.

While the market may not crash anytime soon, it’s important to keep your head when investing, make sensible decisions, and not get swept up in the latest fad or panic.

And what would a comment on equity markets be without a quote from Warren Buffet? ‘Be Fearful When Others Are Greedy and Greedy When Others Are Fearful.’

There will always be a bear

As the old saying goes, “what goes up must come down”. There will always be market pullback, because bull markets don’t last forever.

Growth can continue, but it’s never a smooth path – since 1928, the S&P 500 Index in the US (a key barometer of large US stocks) has declined 10% or more from a recent high more than 90 times, with just a handful of years not recording a 10% dip, according to ASA analysis.

So, while on average the Australian equities market has increased at 8-9% over the past 20 years, it has not been without the occasional shock.

In volatile times you may feel that your portfolio is shrinking, but history shows that markets tend to recover.

The key is to focus on the destination, not the road. Don’t sell your shares immediately just because a company has had a bad day – block out the “market noise” and stick to your financial plan.

Don’t jump into a new stock just because the crowds are promoting it, don’t sell an existing stock just because the crowds dismiss it.

Stay rational. Make your own decisions.

Don’t panic!

Remember that a loss is only on paper unless you crystallise it.

Just because markets are volatile, it doesn’t mean that you must sell out.

For most of us who aren’t speculators, shares should be treated as a longer-term asset – at least three years and probably longer, in ASA’s view.

Even if you need to convert to cash at a particular time, you can still pick your moment – some dips are brief, some last longer, but all of them end.

Have an investment plan

It is important to have a flexible investment plan that recognises that markets change and that you, as the investor, will go through different life stages.

For example, should you anchor your investing decision-making to an old price and ignore new information, or do you factor in the latest results?

Some investors hold on too long, hoping that the share price will recover, rather than selling at a loss and investing in another company that will deliver dividends or growth. Others may sell too soon.

Sometimes it is harder to do nothing than to make a quick decision based on market conditions. But then, “act in haste, repent at leisure”.

Occasional losses are part of life, and your investment plan should recognise this. For example, my plan is to buy and hold good companies, with strong management teams, that have a good strategy and could perform well in the long term.

I am not trying for a quick win but am looking for share price growth and a dividend reinvestment plan that will build the size of my portfolio over the longer term.

Others may choose to have a higher risk strategy, but this leaves them more susceptible to the whims of the market. This may mean having additional rules for investing that recognise the potential for loss – such as greater diversification and stricter limits on how much of your portfolio is exposed to the risky investments.

If your plan is to retire at a certain age, you might need to adapt in volatile times, rather than just selling at a predetermined point. But your plan will help to guide you, because you should know what risk you’re willing to accept and how you will deal with it.

Invest regularly

Sometimes it’s better to invest money periodically, rather than buying up big all at once.

If you have some cash set aside, you’re in a better position to take up stock in a new company or to consider investing when others are spooked by the market and prices are lower.

Remembering it’s not the timing of the market, it’s the time in the market that counts, that will help you to avoid making rash decisions in volatile times and to gain from the power of compounding returns.

Don’t forget tax, and get advice

Consider your tax implications when selling shares, and make sure you’ve set aside money to pay for any capital gains tax (CGT) obligations.

Consider matching the sale of loss-making stocks with purchases of profitable shares to generate the amount of cash required for whatever the cash is earmarked for.

Getting financial advice before you make big investment decisions may help you reach your goals and taxation advice may help protect you unexpected tax bills.

But make sure your financial planner or accountant is qualified and do your own research too – it’s your money, not theirs.

Inform yourself

Sometimes it helps to be part of a larger group. Fellow investors can give you tips on what to do and how to avoid the traps (investments strategies, not stock tips).

If you currently feel unconnected (within investing), consider joining the Australian Shareholders’ Association and its more than 6,000 members?

Our education events and member groups can expose you to new ideas and different investment vehicles, informed by some of the leaders of the investment sector.

The ASA is here to support and represent retail investors, and would love to welcome you into its community.

Econosights – five long-term global trends and implications for markets

Diana Mousina, Senior Economist, AMP

Key points

– In the short-term, economic growth and investment markets are driven by central bank interest rates, government fiscal policy, population growth, productivity and the rate of participation in the labour force.

– But, structural trends are also important in influencing long term economic outcomes, despite being slower moving.

– We outline five major global trends that will influence economic growth and investment markets over coming years.

Introduction

This Econosights looks at some longer-term structural trends in the economy and their impact on economic growth and investment markets.

-

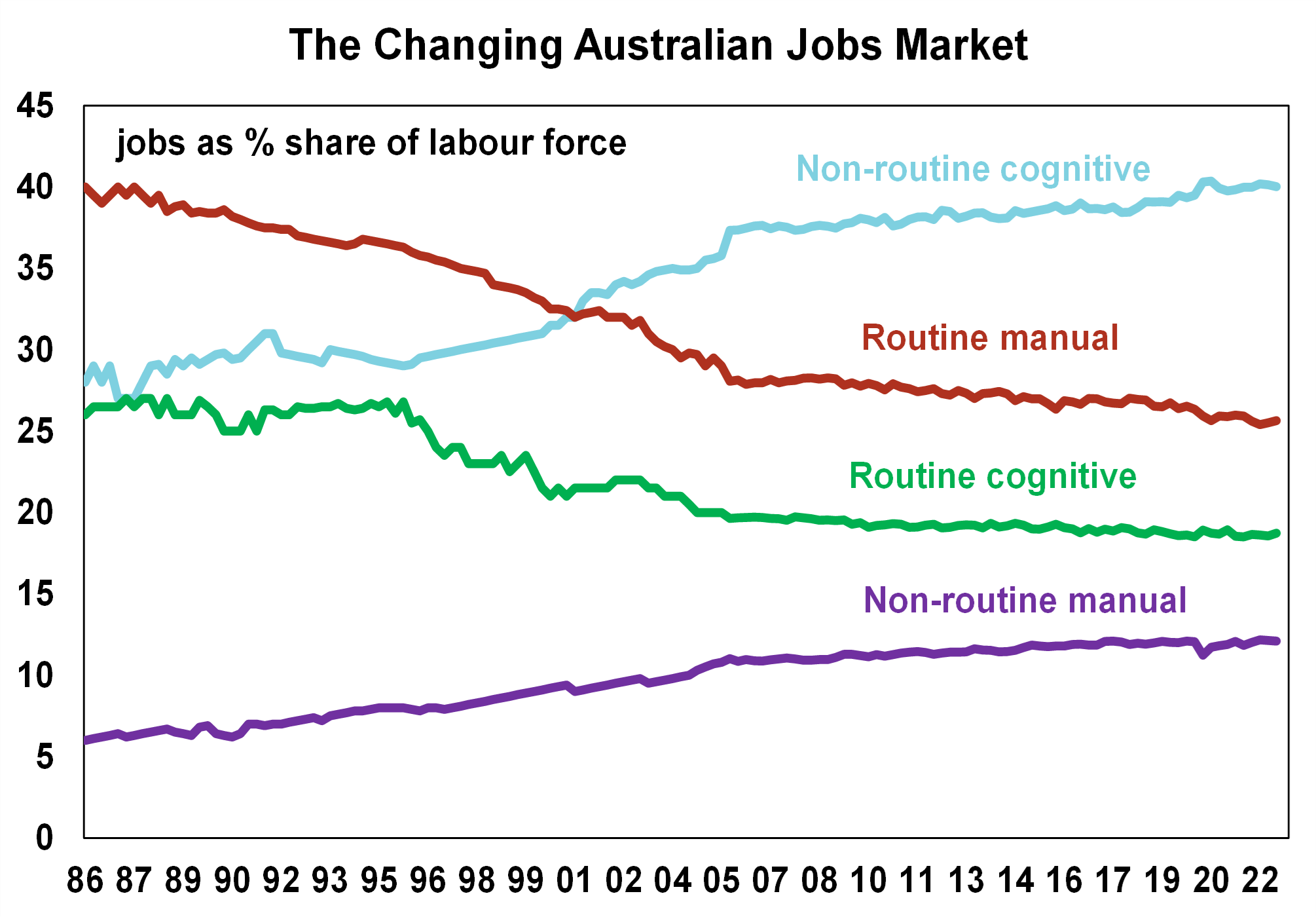

A decline in routine-based jobs

Fear of technology replacing jobs has been around for years, although concern around this risk appears to have waned in recent times, as impacts of the pandemic on labour markets has taken focus. New technology is constantly displacing some jobs, but it is also creating new ones in its place. The jobs most at risk are routine-based jobs, because this type of work can be replicated, learned and taught by machinery and automatic intelligence. In Australia, there has been a long-term decline in manual and cognitive routine based jobs. In the late 1980’s, routine manual jobs were 40% of the workforce and are now around 26% of the workforce while routine cognitive jobs were 26% of the workforce in the late 1980’s and are now worth 19% – see the chart below. Similar medium-term trends are evident across other developed countries. Non-routine jobs (either manual or cognitive) are less at risk of being displaced by technology because they are harder to replicate and often need a human element (for example in jobs related to health, childcare or teaching). Problems in recent years with self-driving cars also shows the difficulties associated with technology.

Middle-income households tend to be most susceptible to routine-based jobs so this trend will increase inequality and could put downward pressure on wages growth in the long-run. The OECD (in a report done in 2018) estimated that around 14% of jobs (in the OECD) are at high risk from automation, with large variations across countries (countries that are higher at risk include Slovakia, Slovenia, Greece and Spain while the countries at the lowest risk include Norway, Australia, Finland and Sweden). The workforces that are more at risk tend to have a lower-educated workforce, a weak tradeable services sector and have a low urbanisation rate. In Australia, around 7% of jobs are estimated to be at high risk of automation and in the US its slightly higher at 10%. The government has a role to play in ensuring that the transition to new types of employment for impacted employees is managed through training programs, appropriate university curriculum and ensuring that funding is targeting those areas at the highest at risk of job losses due to automation.

Source: ABS, AMP

-

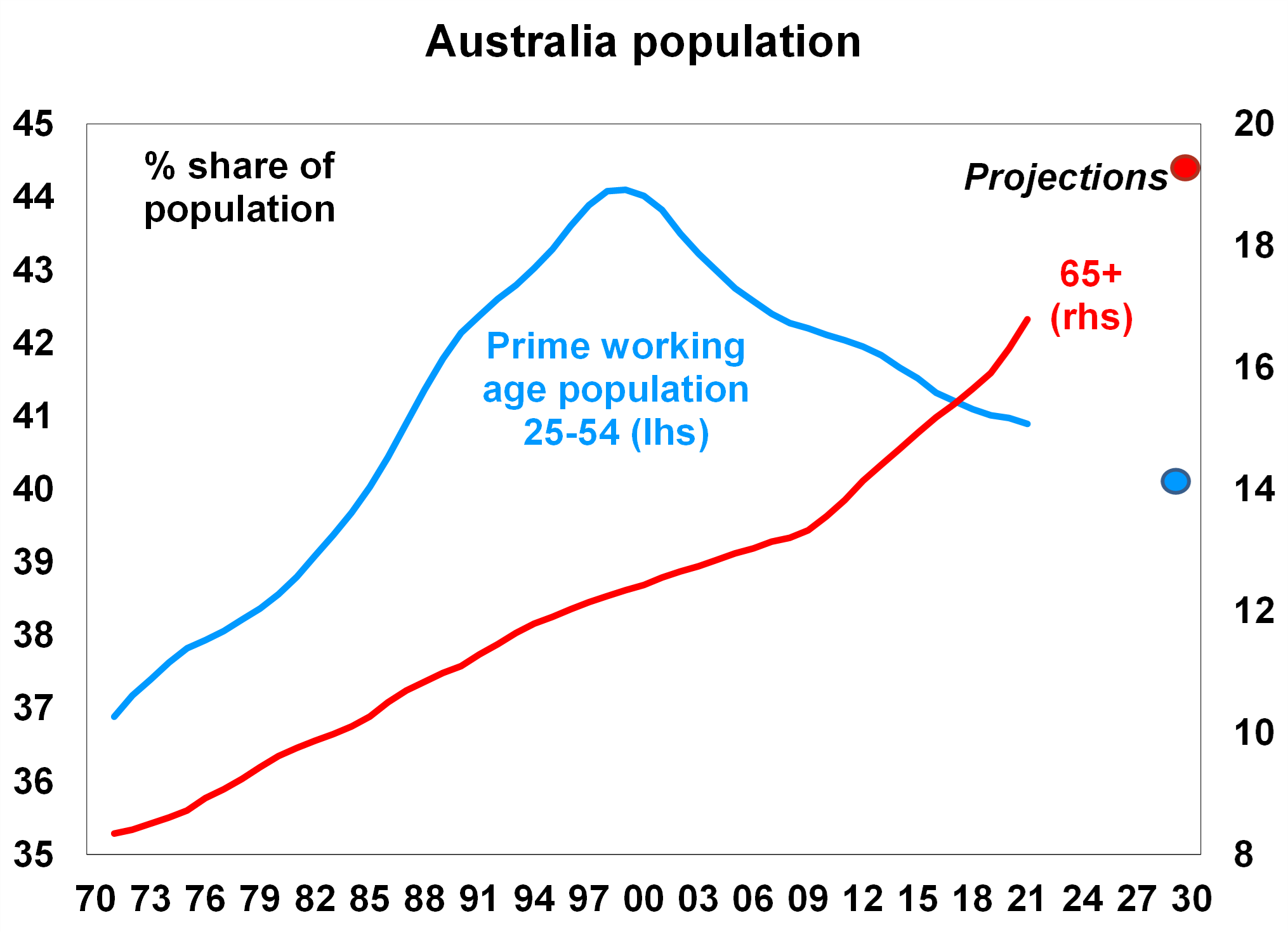

An ageing population and an increase in the “dependency ratio”

The global population, especially in major developed countries, is ageing which has been a long-term trend as the birth rate has declined. In Australia, the share of the prime working age population (those aged between 25-54) peaked at 44% of the population in 1999 and has been falling slowly since then, currently at around 41% and projected to be around 40% by the end of the decade. In contrast, the share of the population that is aged 65+ is expected to keep climbing to just under 20% by 2030, up from 17% now (see the chart below). An aging population will put upwards pressure on the “dependency ratio” (the sum of those aged under 15 and over 65 as a share of the whole population) which will detract from national savings (people who work increase savings while the very young and old drain savings) which is inflationary in the long-term.

Source: ABS, AMP

-

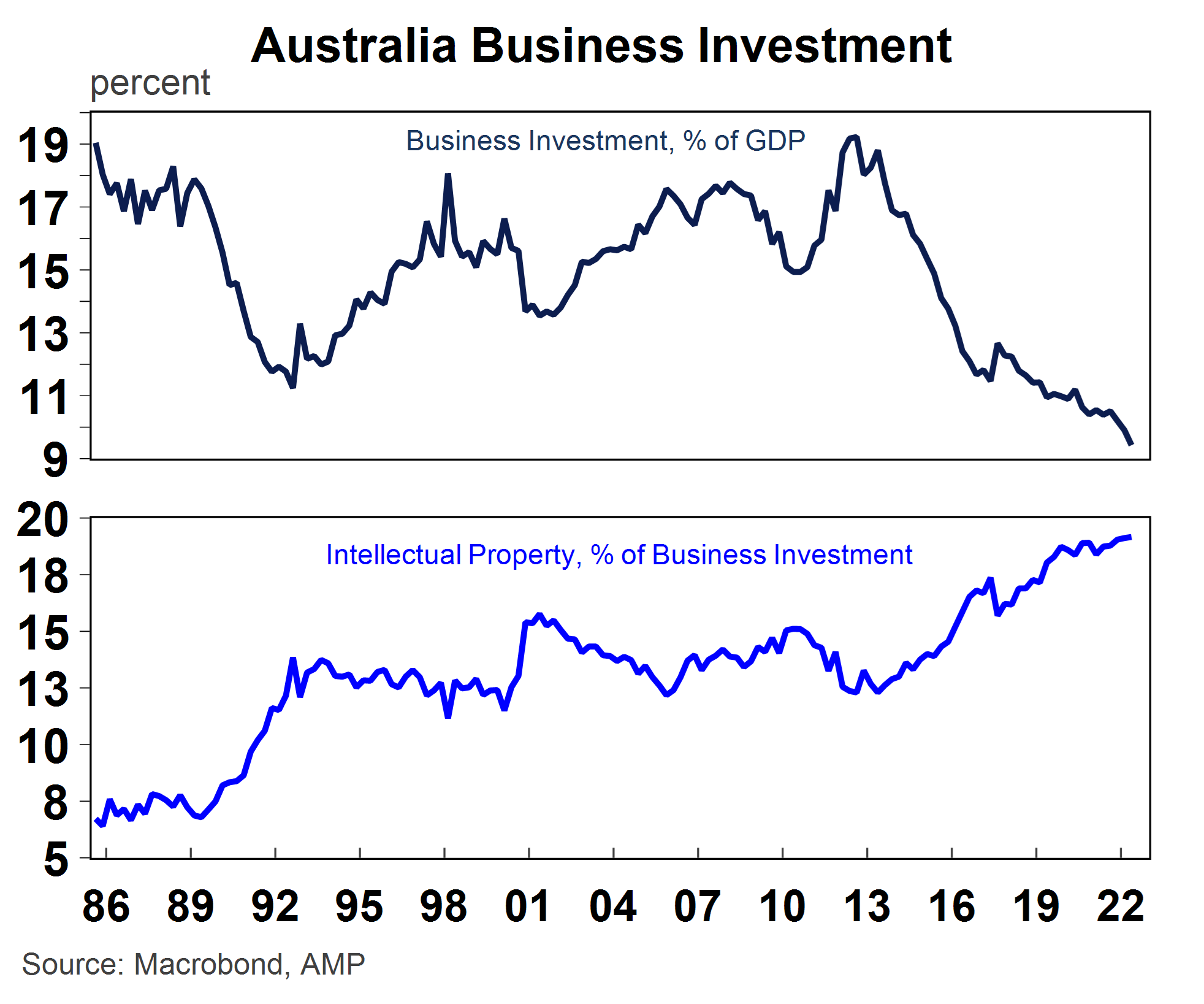

A decline in business investment as a share of GDP but a lift in intellectual property as a share of investment

In many developed countries, private business investment is declining as a share of the economy, in place of a rising services sector which is less investment intensive. In Australia, business investment often goes through cycles because of the dominance of the mining sector (at its peak mining investment reached 11% of GDP). After the last mining investment boom (which ended in 2012 after business investment was 19% of GDP), investment has been on a gradual decline and is now 9.4% of GDP (see the chart below). While there may be ups and downs in the cycle from the mining investment contribution and the usual wear and tear associated with depreciation, private business investment is likely to decline further as a share of GDP because of the changing nature of business investment. The typically large-scale buildings and structures, machinery and equipment type of investment is being replaced with less “heavy” types of investment, like intellectual property with the rising importance of the tech sector in all industries. A less capital-intensive economy could weigh on long-run productivity growth, although the impact is probably marginal as intellectual property investment should still boost productivity growth.

Source: Macrobond, AMP

-

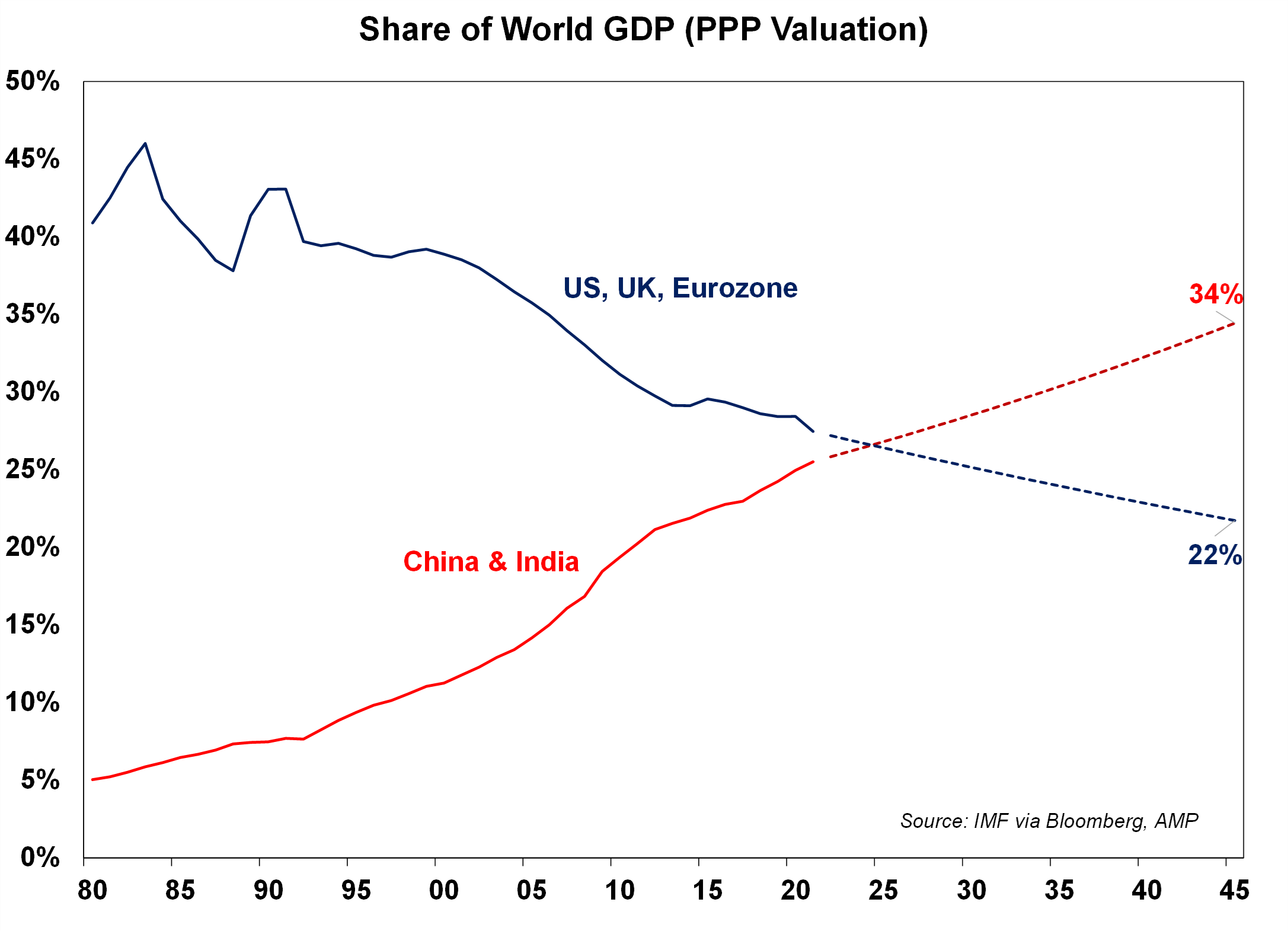

A multi-polar world means more geopolitical risks

The US economy has been increasing in importance to the global economy since the end of the Second World War. The rising significance of the US economy to global trade, cultural influences, military presence and economic power has been increasingly consistent with a unipolar world, especially as the United Kingdom and the Eurozone have had challenging economic conditions in the past decade.

However, the balance of power has been shifting in recent years as the Chinese economy grows and becomes a larger share of the global economy (see the chart below). In purchasing power parity (PPP) terms (which adjusts individual country prices into a global comparison after accounting for exchange rates and purchasing power in each country which allows a better sense of living standard comparison) the Chinese economy is already the largest in the world (at 19% versus the US at 16%). If we also account for India then China and India make up 26% of the global economy compared to the US, UK and the Eurozone at 27% (in PPP terms). But we are currently at a crossroads, with China and India about to takeover as a larger share of the global. On our estimates China and India will be 34% of the global economy by 2045, versus 22% for the US, UK and Eurozone (if growth rates continue at its current pace). As a result, the global economy is increasingly moving towards a multi-polar world as the balance of power shifts away from the US. This shift in the balance of power will keep geopolitical tensions and risks high over coming years as the US and China compete for global control, particularly in the technological space. Investors should be prepared for periodic inflammations in geopolitical tensions and heightened risks of conflict or war, keeping volatility in sharemarkets high. Concerns over the growing Chinese economy are expected to again be a feature of both the Democratic and Republican party campaigns in the 2024 US Presidential election. However, in Australia, the relationship with China looks to be improving with a recent meeting between Australian PM Albanese and China’s President Xi Jinping seemingly the most positive in years.

Source: World Bank, AMP

-

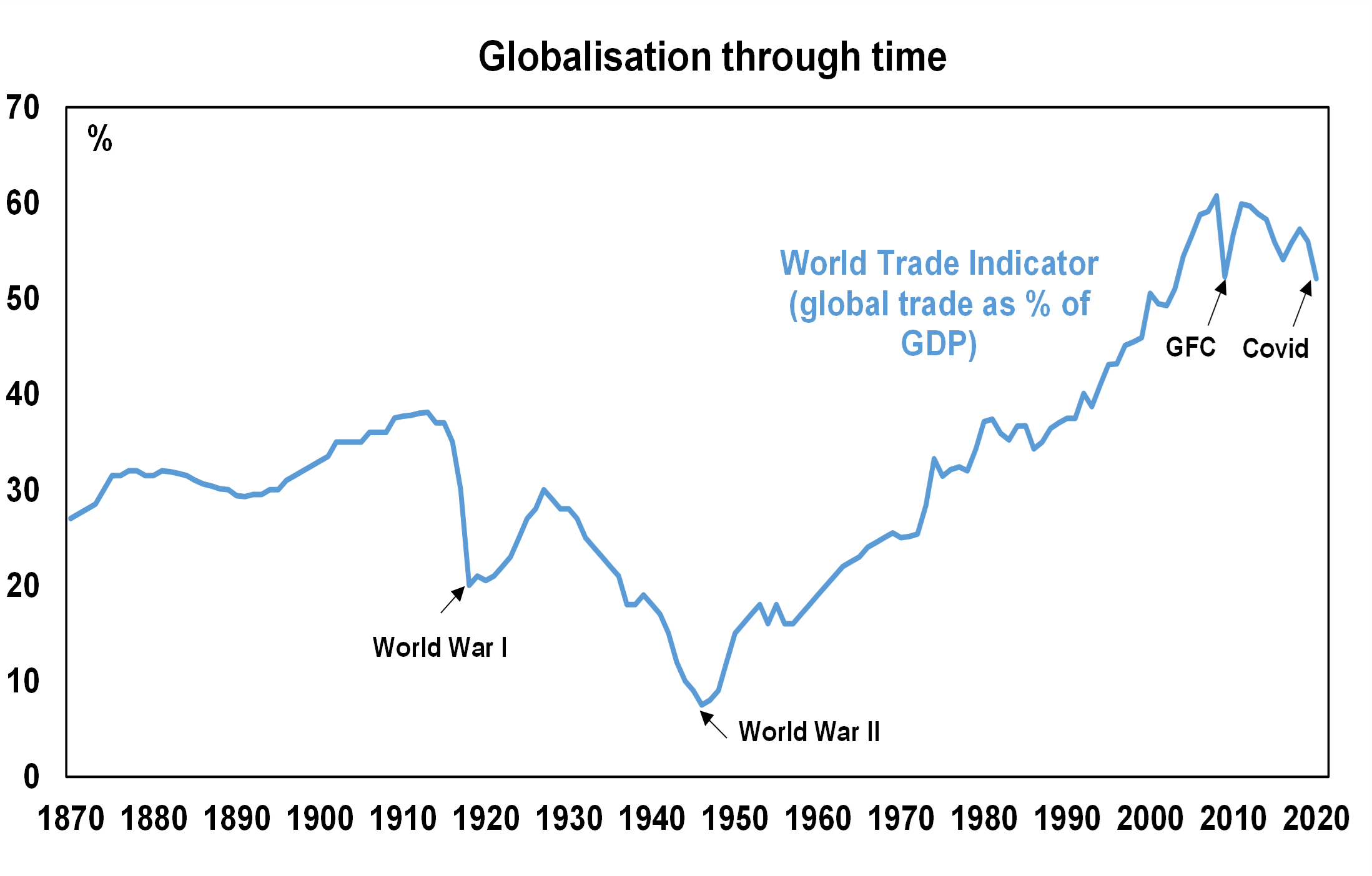

Peak globalisation is inflationary

Globalisation looked to be reaching a peak before Covid-19 broke out, with global trade (the sum of exports and imports) declining as a share of GDP since the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 (the chart below shows that global trade was 56% of GDP in 2019, below its peak of ~61% before the GFC), as countries decided to become more self-sufficient after seeing the contagion impacts of the GFC. Covid-19 dealt another blow to global trade as closed borders and transport delays led to a push towards bringing as much production onshore as possible, or at least to closer countries (“nearshoring” or “friendshoring”). Given that globalisation was disinflationary because production was transferred to countries to the most efficient producer (which most often ended up being the lowest-cost producer) some reversal in the globalisation trend will be more inflationary for the global economy.

Source: World Bank, BCA, AMP

I hope you have enjoyed this week’s report. Please feel free to contact us to discuss your investment requirements.

Regards,

Chris Hagan.

Head, Fixed Interest and Superannuation

JMP Securities

Level 1, Harbourside West, Stanley Esplanade

Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea

Mobile (PNG):+675 72319913

Mobile (Int): +61 414529814